Support Your Journey

Where Are You in Your Menopause Journey?

Take Our Quiz

As we transition into perimenopause, then menopause our body composition and weight is mainly driven by our hormones. Our hormones are influenced dramatically by the quality of the foods we eat, and less by the quantity.

Hormones determine your level of hunger, your level of satiety, how and where you store fat, and how and when you burn fat. Non-optimal levels of these hormones are linked to obesity, chronic inflammation, heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

The interaction between hormones is complicated, especially during menopause. Fortunately, we can support our hormone production, fight inflammation, weight gain, and obesity through simple, nutritional choices.

Top 10 Tips For Optimizing The Hormones That Control Your Weight In Menopause

Limit Carbohydrates

Lowering your intake of simple and refined carbohydrates has been proven to lower insulin levels and stabilize blood sugar levels. This includes limiting pastas, rice, breads, baked goods, processed and or boxed foods. Don’t ditch the carbs though! Choose complex carbs that come from the earth: fruits and vegetables, whole grains and legumes. Not only are they nutrient dense, but they are full of fiber.. 1- 3

Limit Or Avoid Added Sugars

High amounts of ADDED sugars, especially high fructose corn syrup, sweetened beverages and some cocktails, promote insulin resistance, and raise insulin, ghrelin, and cortisol levels. Added sugars are the sugars added in cooking and processing, not the sugars naturally found in fruits, vegetables, and dairy products. 4- 6

Learn how to reduce your consumption of sugar with our 10 Day Sugar Detox.

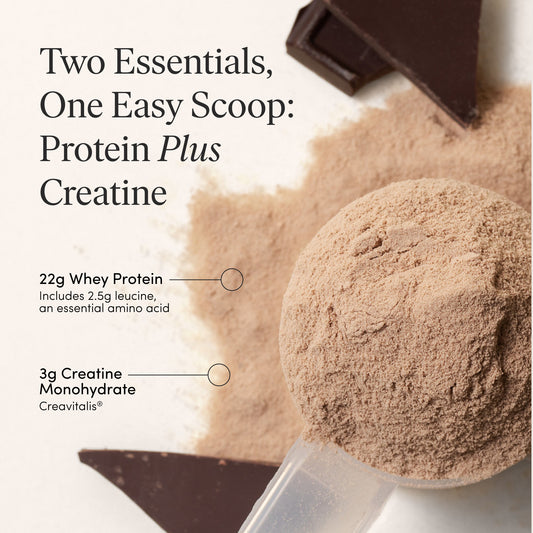

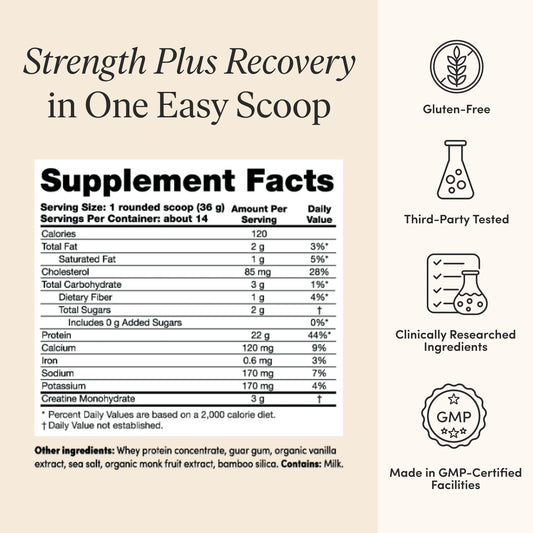

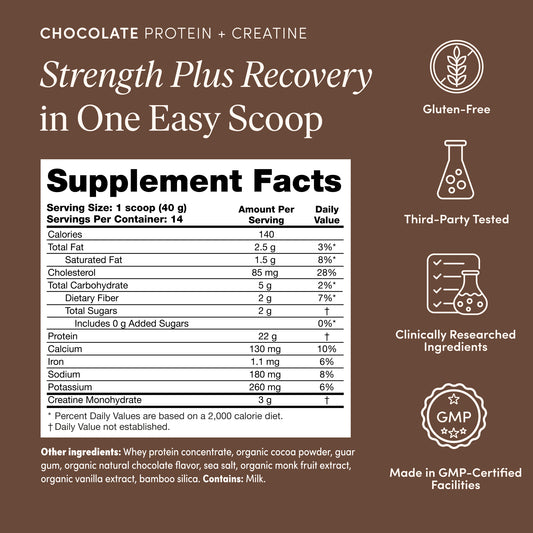

Eat Protein

Although insulin levels rise initially after eating protein, the long-term effects of eating protein throughout your eating window can lead to a decrease in belly fat and insulin resistance, while also improving leptin resistance and decreasing Ghrelin levels. Balance protein consumption throughout the day and aim for at least 20 – 25g with each meal. 7-9

Hot tip: Use this protein calculator to determine your specific protein needs and divide your needs over the course of your daily meals and snacks. Supplement with a high quality protein powder when necessary.

Eat Healthy Fats

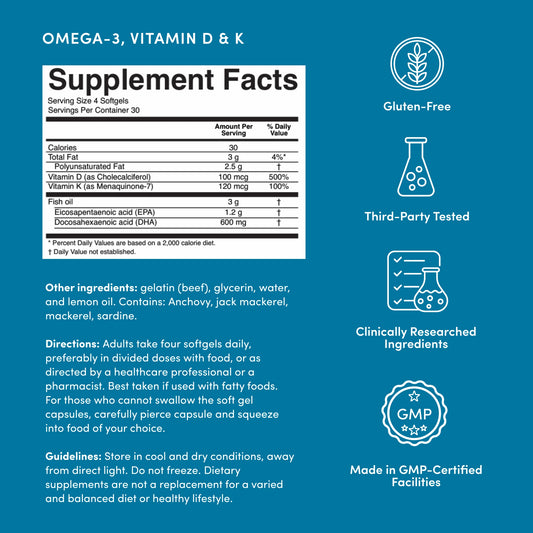

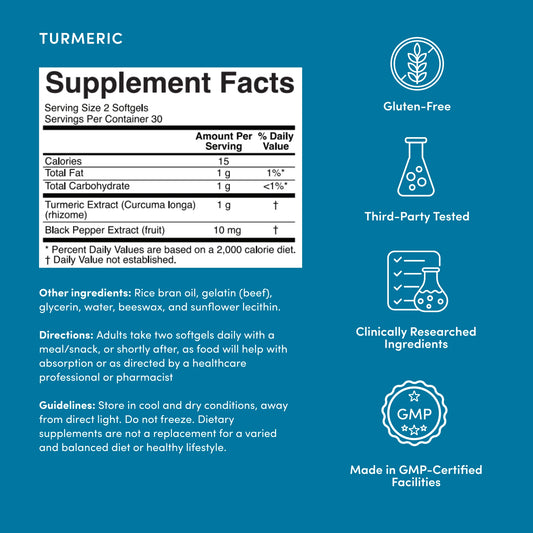

Omega-3 rich foods have been found to help lower fasting insulin and cortisol levels and stimulate the production of cholecystokinin, which is a natural appetite suppressant. Omega-3 rich foods include fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel and sardines, seeds, especially flax, chia and hemp, walnuts, as well as grass fed proteins and omega 3 enriched eggs. Supplementing with a high quality omega-3 supplement is a great way to consume at least one high quality source of omega-3 each day.10-12

Exercise Regularly

Aim for a total of 150 minutes of cardiovascular exercise a week, divided into 3 or more sessions to improve insulin sensitivity and decrease cortisol levels. Strength training, yoga, and/or Pilates is critical to overall health. Doing some sort of resistance training 2 or more days per week has a lasting impact on weight management thanks to the maintenance, strengthening and building of muscle tissue. 13-14

Probiotics

Your body, especially your large intestine, contains trillions of microorganisms. The gut microbiota, a colonic bacterial population, plays a role in immunological health, digestion, and other bodily processes. Probiotics are good bacteria that are comparable to those found naturally in the body and are available through nutrition and/or supplementation. Some foods high in probiotics are yogurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, kefir, tempeh, miso and pickled vegetables. Incorporating probiotics to promote a healthy gut biome has been shown to lower cortisol levels. Read more here.

Get Enough Soluble Fiber

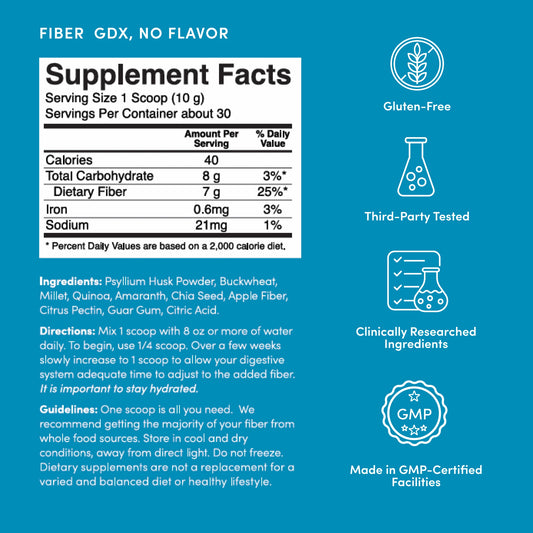

Fiber is a prebiotic – and promotes a healthy gut biome. Track your total fiber intake and ensure you are getting at least 25 mg (for women the goal is 25-35 mg/day) . Supplement if needed with a product that contains both soluble and insoluble fiber, such as The 'Pause Nutrition Fiber GDX. This improves fasting blood sugars which improve insulin resistance. This also contributes to a healthy gut biome which through reduction in leaky gut syndrome, can improve leptin resistance and decrease cortisol levels. Fiber intake also stimulates CCK which is a potent appetite suppressant. 15-21

Limit Processed Foods

Processed food led to inflammation while increasing the risk of developing diseases like arthritis, asthma, cardiovascular disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, type 2 diabetes and more. A diet with few processed foods is less likely to produce leptin resistance and more likely to control chronic inflammation. For a more in-depth understanding of inflammation, pick up a copy of The Galveston Diet book or enroll in The Pause Strong Program.

Get Quality Sleep

Sleep is the great restorer. Quality sleep is correlated with lower leptin resistance and reduces cortisol levels. It allows our cortisol to lower, aids in healing, allows for full digestion, and resets our mental capacity, improving symptoms of brain fog and our ability to manage stress. 30-33

Consider Cinnamon, Apple Cider Vinegar, And Magnesium

Each of these has been shown in some studies to lower fasting glucose levels, insulin levels and improve insulin resistance. While they do not directly cause weight loss, there are benefits that can support hormone levels and weight management efforts.

Bonus! Dark Chocolate

(70% cacao or darker with no artificial additives and/or colorings) and Black/Green tea have been shown to lower cortisol levels in response to stress.

The Belly Fat Blast and 'Pause Strong Challenges or The Galveston Diet book and The Pause Strong Program can provide the structure and accountability you need to put these nutritional and lifestyle habits into practice, making it easier to manage symptoms and support your health through menopause. You can also connect with us in our free community, where you’ll find accountability, shared experiences, and inspiration every day.

Sources:

- Havel P. J. (2004). Update on adipocyte hormones: regulation of energy balance and carbohydrate/lipid metabolism. Diabetes, 53 Suppl 1, S143–S151. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s143

- Bosma-den Boer, M.M., van Wetten, ML. & Pruimboom, L. Chronic inflammatory diseases are stimulated by current lifestyle: how diet, stress levels and medication prevent our body from recovering. Nutr Metab (Lond) 9, 32 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-32

- Nettleton,JA, Steffen,LM, Mayer-Davis, EJ, Jenny,NS, Jiang, R, Herrington,DM, Jacobs, DR. (2006) Dietary patterns are associated with biochemical markers of inflammation and endothelial activation in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 83(6), P 1369–1379, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1369

- Luger, M., Lafontan, M., Bes-Rastrollo, M., Winzer, E., Yumuk, V., & Farpour-Lambert, N. (2017). Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Weight Gain in Children and Adults: A Systematic Review from 2013 to 2015 and a Comparison with Previous Studies. Obesity facts, 10(6), 674–693. https://doi.org/10.1159/000484566

- Stern, D., Middaugh, N., Rice, M. S., Laden, F., López-Ridaura, R., Rosner, B., Willett, W., & Lajous, M. (2017). Changes in Sugar-Sweetened Soda Consumption, Weight, and Waist Circumference: 2-Year Cohort of Mexican Women. American journal of public health, 107(11), 1801–1808. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304008

- Lee, A. A., & Owyang, C. (2017). Sugars, Sweet Taste Receptors, and Brain Responses. Nutrients, 9(7), 653. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070653

- Schwarz, N. A., Rigby, B. R., La Bounty, P., Shelmadine, B., & Bowden, R. G. (2011). A review of weight control strategies and their effects on the regulation of hormonal balance. Journal of nutrition and metabolism, 2011, 237932. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/237932

- Maltais, M. L., Desroches, J., & Dionne, I. J. (2009). Changes in muscle mass and strength after menopause. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions, 9(4), 186–197.

- Rizzoli, R., Stevenson, J. C., Bauer, J. M., van Loon, L. J., Walrand, S., Kanis, J. A., Cooper, C., Brandi, M. L., Diez-Perez, A., Reginster, J. Y., & ESCEO Task Force (2014). The role of dietary protein and vitamin D in maintaining musculoskeletal health in postmenopausal women: a consensus statement from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Maturitas, 79(1), 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.07.005

- Schwarz, N. A., Rigby, B. R., La Bounty, P., Shelmadine, B., & Bowden, R. G. (2011). A review of weight control strategies and their effects on the regulation of hormonal balance. Journal of nutrition and metabolism, 2011, 237932. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/237932

- Bosma-den Boer, M.M., van Wetten, ML. & Pruimboom, L. Chronic inflammatory diseases are stimulated by current lifestyle: how diet, stress levels and medication prevent our body from recovering. Nutr Metab (Lond) 9, 32 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-32

- Tartibian, B., Hajizadeh Maleki, B., Kanaley, J. et al. Long-term aerobic exercise and omega-3 supplementation modulate osteoporosis through inflammatory mechanisms in post-menopausal women: a randomized, repeated measures study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 8, 71 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-8-71

- Schwarz, N. A., Rigby, B. R., La Bounty, P., Shelmadine, B., & Bowden, R. G. (2011). A review of weight control strategies and their effects on the regulation of hormonal balance. Journal of nutrition and metabolism, 2011, 237932. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/237932

- Tartibian, B., Hajizadeh Maleki, B., Kanaley, J. et al. Long-term aerobic exercise and omega-3 supplementation modulate osteoporosis through inflammatory mechanisms in post-menopausal women: a randomized, repeated measures study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 8, 71 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-8-71

- Mantzoros C. S. (1999). The role of leptin in human obesity and disease: a review of current evidence. Annals of internal medicine, 130(8), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-130-8-199904200-00014

- Lee, A. A., & Owyang, C. (2017). Sugars, Sweet Taste Receptors, and Brain Responses. Nutrients, 9(7), 653. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070653

- Yu, K., Ke, M. Y., Li, W. H., Zhang, S. Q., & Fang, X. C. (2014). The impact of soluble dietary fibre on gastric emptying, postprandial blood glucose and insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition, 23(2), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.2014.23.2.01

- Beck B. (2006). Neuropeptide Y in normal eating and in genetic and dietary-induced obesity. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 361(1471), 1159–1185. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2006.1855

- Beglinger, C., & Degen, L. (2004). Fat in the intestine as a regulator of appetite–role of CCK. Physiology & behavior, 83(4), 617–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.07.031

- Little, T. J., Horowitz, M., & Feinle-Bisset, C. (2005). Role of cholecystokinin in appetite control and body weight regulation. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 6(4), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00212.x

- Batterham, R. L., & Bloom, S. R. (2003). The gut hormone peptide YY regulates appetite. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 994, 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03176.x

- Lee, A. A., & Owyang, C. (2017). Sugars, Sweet Taste Receptors, and Brain Responses. Nutrients, 9(7), 653. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070653

- Yu, K., Ke, M. Y., Li, W. H., Zhang, S. Q., & Fang, X. C. (2014). The impact of soluble dietary fibre on gastric emptying, postprandial blood glucose and insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition, 23(2), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.2014.23.2.01

- Arnold, K., Weinhold, K. R., Andridge, R., Johnson, K., & Orchard, T. S. (2018). Improving Diet Quality Is Associated with Decreased Inflammation: Findings from a Pilot Intervention in Postmenopausal Women with Obesity. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 118(11), 2135–2143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2018.05.014

- Poti, J. M., Braga, B., & Qin, B. (2017). Ultra-processed Food Intake and Obesity: What Really Matters for Health-Processing or Nutrient Content?. Current obesity reports, 6(4), 420–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0285-4

- Cavanagh, M. M., Weyand, C. M., & Goronzy, J. J. (2012). Chronic inflammation and aging: DNA damage tips the balance. Current opinion in immunology, 24(4), 488–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2012.04.003

- Myles I. A. (2014). Fast food fever: reviewing the impacts of the Western diet on immunity. Nutrition journal, 13, 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-61

- Nettleton,JA, Steffen,LM, Mayer-Davis, EJ, Jenny,NS, Jiang, R, Herrington,DM, Jacobs, DR. (2006) Dietary patterns are associated with biochemical markers of inflammation and endothelial activation in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 83(6), P 1369–1379, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1369

- Minihane, A., Vinoy, S., Russell, W., Baka, A., Roche, H., Tuohy, K., . . . Calder, P. (2015). Low-grade inflammation, diet composition and health: Current research evidence and its translation. British Journal of Nutrition, 114(7), 999-1012. https://doi:10.1017/S0007114515002093

- Schwarz, N. A., Rigby, B. R., La Bounty, P., Shelmadine, B., & Bowden, R. G. (2011). A review of weight control strategies and their effects on the regulation of hormonal balance. Journal of nutrition and metabolism, 2011, 237932. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/237932

- Brain basics: Understanding sleep. (2023). National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute of Health. Retrieved from:https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/public-education/brain-basics/brain-basics-understanding-sleep

- Stern, J. H., Grant, A. S., Thomson, C. A., Tinker, L., Hale, L., Brennan, K. M., Woods, N. F., & Chen, Z. (2014). Short sleep duration is associated with decreased serum leptin, increased energy intake and decreased diet quality in postmenopausal women. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 22(5), E55–E61. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20683

- Kravitz, H. M., Kazlauskaite, R., & Joffe, H. (2018). Sleep, Health, and Metabolism in Midlife Women and Menopause: Food for Thought. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America, 45(4), 679–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2018.07.008